Waiting in the lift on the 5th floor at Chiang Mai Ram hospital, my colleagues were noticeably anxious, though when the lift pinged open on the 7th floor, and seeing a few kids chuck around plastic building bricks in a play pen, they breathed a sigh of relief…the floor was obviously unhaunted and in-use.

We were on a mission. We were looking for a mysterious 13th floor, which was rumoured to be a sepulchral halfway house inhabited by the dead…according to Chiang Mai urban legends. The 12th floor was eerily quiet, and opening doors to dusty ward rooms and seeing all the empty beds where countless dead might have laid, felt slightly criminal as well as morbidly spooky. On noticing we were being watched by CCTV wandering around and trying doors we made a hasty exit, but not before we checked the roof for evidence of (suicidal?) spooks. Through the crack in the door all there was to see was blue sky.

Our spiritual sleuthing skills have determined that in spite of the ‘common knowledge’ concerning the ghost floor – frequency of death in a hospital warrants not just a spirit house, but an entire floor, we might say a ‘spirit level’ – it is in fact just a little bit specious.

The haunted dorms at Chiang Mai University (filmed in the movie Ma Ha Lai Sa Yong Kwan). It’s also said that if you drive around the CMU clock tower three times in the wrong direction you’ll open up a vortex into some kind of ghost world.

The old railway station hotel (now destroyed, so unless the former inhabitants are roughing it on the new park benches that replaced the hotel they may now haunt another place) was verily haunted and very much talk of the town on the ghost scene for years.

My personal favourite, Laddaland – an area just off the Irrigation Canal Road close to the Phucome Junction where abandoned houses are/were not only home to ghosts and old roller-skates rattling in the wind, but Thai teenagers shooting up meth, smack and Drano. Think ‘The Wire’ with ghosts. And if the kids end up ODing on a doorstep, they don’t have far to travel to hang out in druggy purgatory. Laddaland is also a kind of rite of passage place for teens who dare to enter somewhere haunted. Unfortunately for the gangs of kids, and the bands of ghosts, the municipality has grand ideas for Laddaland. Move on, move on, move on, say the authorities.

And there is no shortage of condos in the city that stand perpetually in financial crisis, filled with the dreams of assassinated, or destitute developers, that cast morbid shadows neighbouring communities.

Chiang Mai even has its – brace yourself – house of horrors where it’s said the husband of a rich family went irreversibly crackers, and in a fit of irrational jealously and hurt pride he chopped his wife and kids up into untidy parcels of human flesh – consistent so far with the daily news and hardly worth the turn of your head, though the twist is the family still reside there all worked up and pissed off at having left terra firma in such violent and bloody circumstances. Go see for yourself, it’s the gothic style edifice, replete with gargoyles and other statues on the corner of the moat next to Chiang Mai Bowling.

The Age of Reason

The myth of Mae Nak, comic Casper (the friendly ghost), and the film Paranormal Activity – Parts I and II – are forms of entertainment on the one hand, serving our superstitions well. On the other hand ghost stories, the bogey man, are, and have been, used to police the masses, often through benign morality tales (don’t swear or the ghost will get you, says Somchai’s mother). Fake ghosts are often created in Thailand so that innocent folk in moments of pecuniary desperation pay large amounts of money to venal monks or quack shaman who might contact the dead and ask for the upcoming lottery numbers. So while theologians, eschatologists (study of afterlife and ‘ends’) and experimental psychologists sweat it out thinking about life after death and the apparentness of apparitions, the public’s great stake in the possibility of the existence of ghosts should not be underestimated.

At Chiang Mai University’s department of philosophy and religion I spoke with Asst. Prof. Dr. Viraj Inthanon. The doctor, who had been a monk for 14 years, explained how Thai superstitions and Buddhism had become enmeshed in Thailand. “There is a book that translates something like the ‘Origins of Ghosts in Lanna,'” says Viraj, and this is where he says most people’s beliefs about ghosts comes from. “The book tells how each clan must have a ghost,” he says, which is a form of ancestor (pee poo ya) worship.

Ancestral ghosts are the good (if kept in red Fanta) ghosts, the protective ghosts, in Thai beliefs, dead relatives you propitiate, beg or cajole with food and drinks and sometimes animal sacrifice, and in turn they offer some sort of secular back-up. “In the suburbs,” explains Viraj, “people still make these kinds of offerings.” He tells us how not only the family is protected by the dead, but each village in Chiang Mai will also have a protective ghost, as does our city. According to the ajarn, Lanna tradition believes that our provincial spook, named Jao Lung Kamdaeng, resides in Chiang Dao.

Thailand’s traditional ghost stories, such as the village and ancestral ghosts are widely believed, though they do seem quite anachronous in the age of iPhone, and possibly not as affective to young minds as the likes of the much hackneyed long-haired girl with a double jointed neck that haunts the cinema houses of East Asia. This kind of Joe Bloggs ghost, the girl who died during pregnancy at the last house on the soi or the top floor condo school kid who slashed his own throat to prove a point to his lover, these are the ghosts that keep the younger generation in check.

Dr. Christopher A. Fisher, also of the Philosophy and Religion Department in Chiang Mai University allowed us into his Buddhist Psychology class to interview an abbot, two monks and two lay students on their beliefs, disbeliefs, and utter incuriousness concerning ghosts.

The two lay students were quick to reply in the positive when asked if they believed in ghosts, explaining that “ghosts are in our bodies, in things, in flowers, everywhere,” which is the general precept of animism. Though the abbot, fluently, smiling genially, expressed a different idea: “It’s difficult to explain,” he says, “We have a third eye, which is like a third sense. Some people who can use this third sense maybe they see ghosts, but maybe others don’t.” He expands by saying that beliefs such as the Thai Ghost that lives in trees and on the land (jao ti) in the past has parried capitalists from destroying forests as cutting down trees would ignite the wrath of mean ghosts. “So ghosts can be used for morality,” says the abbot, “in this case to help the environment.” He remains vague whether he actually believes in those ghosts that saved the trees, so I ask him, but do you believe in ghosts? “Personally I don’t believe in ghosts. I haven’t seen one. Though I believe in inner demons, the ghosts inside, ghosts in your mind. These ghosts destroy your life. We should think about the desire that destroys us within, not the things on the outside.” He says that ghosts, as mentioned earlier in this story, play no part in Buddhism.

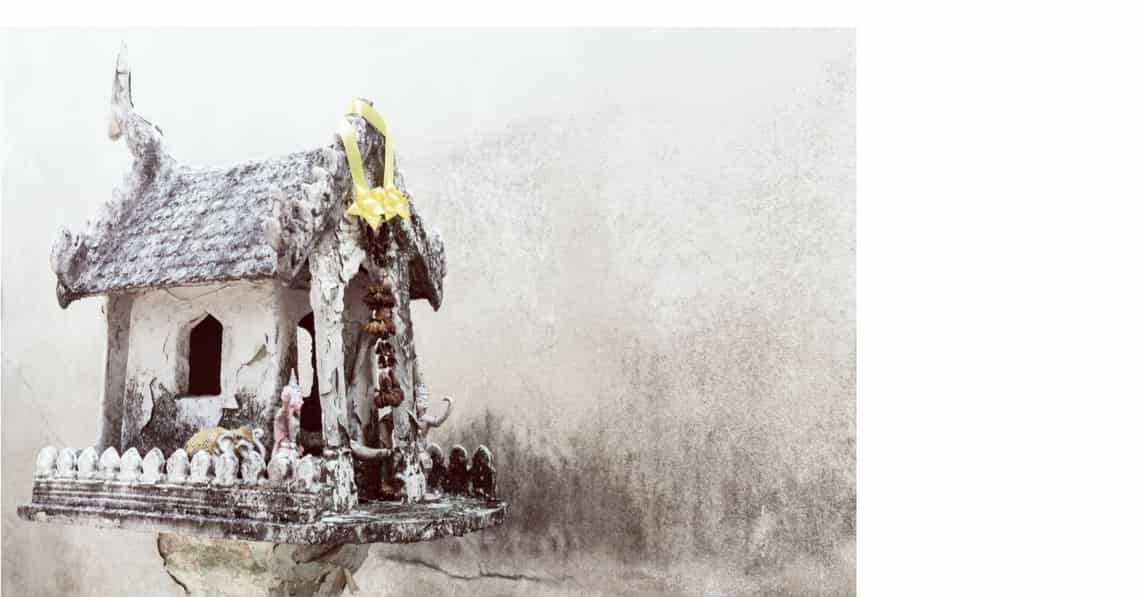

“Everything is natural,” the abbot says, “there is no supernatural.” On reincarnation, he explains that people are unhappy because of their desires, which manifests as their suffering. We are born again in life, going through many rebirths during our lives, and we will live in suffering if we don’t realise the ruinous effects of these desires and annul them. He rejects the often held belief of reincarnation (metempsychosis) that some people subscribe to where we die and possibly come back as lordly lions with fetching manes, or perhaps even ill-starred handicapped worms (depending on things like how many prostitutes you slept with), but that our soul, which is our consciousness, does remain in the universe. Our energy does not just disappear, the abbot thinks. Whether this energy we inhabit the universe with might appear in ghost form is “not important to me,” says the smiling abbot, “Buddhists are not concerned with ghosts, we are concerned with the fears in our hearts.” He explains how Buddhism struggled with superstition in its first couple of centuries in Thailand, though eventually managed to win over many partisan animists and other spectacular believers. As to the belief in popular ghosts such as the spectral village heads or the dead lunatics of Laddaland the abbot replies, “They are good lies, like your Santa Claus lie.” He adds that, “If someone really understands Buddhism they won’t have a spirit house. The spirit house is not Buddhist.” Nevertheless, the lay male student near to him asserts that Thais need the spirit houses for protection.

“Old customs are used to control people. Ghosts are used to control behaviour. But we (Buddhists) believe in freedom, and freedom alone.

Buddhism is like real democracy, no one controls us,” are the emphatic words from the abbot. His empirical philosophy seems to work for him. What he can’t see, and understand, doesn’t concern him, though he’s willing to keep an open mind (eye). Just before I left the classroom I asked the abbot what he thought would happen if someone drove around the CMU clock tower counter-clockwise three times? Would it open a vortex to a spirit world? “No,” he said, unsurprisingly, “you’ll have an accident.”